“Motivation is the fuel, necessary to keep the human engine running.” ― Zig Ziglar

Getting inspired is a wonderful way to get enthusiastic and jump into an endeavor.

However, after the initial inspiration, what keeps you interested and engaged is the motivation that you experience on a daily basis.

What motivates you?

And how can you sustain the motivation to keep your levels of engagement high?

What do science and studies show us about human motivation and behavior?

Here are 7 ways and a model or summary that might assist you in motivating yourself and staying motivated on the long stretch.

1. Awareness And A Deep Understanding Of What,When And The Why Of Motivation

“Take up one idea. Make that one idea your life – think of it, dream of it, live on that idea. Let the brain, muscles, nerves, every part of your body, be full of that idea, and just leave every other idea alone. This is the way to success.” ~Swami Vivekananda

Do you have a clear understanding of what motivates you and what demotivates you? I have found it useful to take a few minutes and figure out exactly the following:

What makes me motivated?

Why do you stay motivated in some activities but do not have motivation in others?

Asking the “why” always takes you to the deeper reasons why you have or lack motivation in something.

One example of this is that you will hear that people want to go for a certain career because the money and fame appeal to them. And then they plunge into careers that do not make them happy and staying motivated becomes very difficult.

A better question to ask is “why” because if earning a lot of money is the real reason and motivation to go after something, we might as well find something that we have some interest in but is still financially viable and profitable.

When do you get motivated?

Are you motivated by stillness or by motion?

Different people get motivated by different things. Some learn by seeing, others by touch and still others by sound. When we are made to stay the course in a modality that we find intrinsically not interesting, staying motivated is very difficult.

Be intentional about motivation. It is a good idea to understand why you are not motivated about something because it shines the light of awareness on what you really want.

Action Tips:

Become intentional with motivation.

Ask: Why, what, when and where do you get motivated.

Allow boredom and demotivation to teach you to move forward in finding what you would like to do.

2. The Search For Meaning In Work And Watching Your Progress Are Great Motivators

“The purpose of life is a life of purpose.”― Robert Bryne

In his TED talk, behavioral economist and scientist Dan Ariely talks about a former student of his who came to visit him and told him his story. The student had been working hard on a presentation for a merger and acquisition at a bank.

He stayed up late and perfected the presentation and the day before it was due, he sent it to his boss. The boss replied back saying that it was a nice presentation but the merger had been cancelled. Upon hearing this, the student became quite depressed knowing that nobody would ever view his labor of love.

Ironically, when he was working hard on completing the presentation and accomplishing a meaningful result, he was quite happy. When his project lost the meaning and purpose that it inherently came with, it lead to de-motivation and depression.

Upshot: Meaning is a great motivator, however small it is. When you make progress and see a project to fruition, you are highly motivated. Conversely, abrupt termination of a labor of love is highly demotivating.

In a research article titled Man’s search for meaning: The case of Legos by Ariely, Kamenica and Prelec, the researchers ask if meaning increases productivity and motivation of work through recognition and purpose.

According to the authors:

“With this goal in mind, our conceptualization of meaning is intentionally basic; we view labor as meaningful to the extent that (a) it is recognized and/or (b) has some point or purpose. Recognition means that some other person acknowledges the completion of the work. Such recognition does not have to be linked to any financial incentives or to any non-tangible rewards such as praise or appreciation. Purpose means that the employees understand how their work might be linked, even tangentially, to some objectives. This does not mean that the workers necessarily endorse or care about these objectives, but only that they can relate their labor to a more general objective. We propose that these twin factors are two of the hidden motivational foundations of meaning-in-labor.”

The Experiments

In the first experiment, all participants were given a sheet with a random sequence of letters and were asked to find 10 repeats of the letters “ss.” The researchers assigned subjects randomly to three groups: Acknowledged, Ignored and Shredded.

Wages began with 55 cents/10 repeats and would decline by 5 cents each time the subject agreed to complete a second page and until they decided to stop and receive payment. The acknowledged group was asked to write their name and that after completion their work would be filed away.

In The ignored condition, subjects were not required to write their names on the sheet and their work was ignored by placing on a big stack of papers. The shredded group had their work immediately shredded.

The results showed that the acknowledged group were the most likely to work until the wage dropped to zero and attempted the most sheets and thus making the most money. The ignored and shredded group did the worst with the ignored group doing a bit better than the shredded group.

In the second experiment, subjects were asked to assemble Bionicle Lego models subject to a decreasing pay schedule beginning from $2 for the first and $1.89 for the second or 11 cents less and so on. Each Bionicle contained of 40 parts and required 10 minutes of easy instruction based assembly.

Subjects were randomly assigned to a meaningful or a sissyphus condition and were unaware of the other condition. In The meaningful condition, assembled models were placed on the desk and a new box was given if the subject chose to continue and the models accumulated as they were built.

In the Sisyphus condition, models were identical but were dissembled immediately after they were built and placed back in a box that was given back to the participant for reassembly if they chose to make more.

The results showed that the meaningful condition group built 11 Bionicles on average when compared to the Sisyphus group which only built 7 on average.

This shows that having a small incentive such as watching their models accumulate and not having their work destroyed after each attempt was enough to significantly improve productivity and performance.

Acknowledging effort and labor has a great motivating effect and influence. Ignoring and shredding people’s performance decreases motivation dramatically.

Action Tips:

Infuse meaning into work, however small it is to self-motivate.

See the results of your performance and labor to stay motivated.

Be aware of giving credit to other people’s performance and realize that shredding or ignoring their efforts is de-motivating them.

To motivate people, pay attention to their work, look at it and then acknowledge by at least saying “uh-huh.” Even this small acknowledgement is enough to motivate people.

Become aware of all the incompletions in your life that are demotivating you: complete them or let them go.

“The great and glorious masterpiece of man is to live with purpose.”― Michel de Montaigne

3. A Labor Of Love, The Ikea Effect

“Inspiration fires you up; motivation keeps you burning.” ― Stuart Aken

In a report titled The “IKEA Effect”: When Labor Leads to Love, Michael I. Norton, Daniel Mochon and Dan Ariely describe the increased valuation of products that you make yourself and when you allow them to completion.

The authors mention the above Bionicle experiment and also the folding of IKEA boxes and the folding of origami where this effect of increase valuation was observed.

According to the authors:

“In a series of studies in which consumers assembled IKEA boxes, folded origami, and built sets of Legos, we demonstrate and investigate the boundary conditions for what we term the ‘IKEA effect’ – the increase in valuation of self-made products. Participants saw their amateurish creations – of both utilitarian and hedonic products – as similar in value to the creations of experts, and expected others to share their opinions.”

Interestingly, the IKEA effect was dissipated when the project was not seen to completion or was destroyed as the Bionicle experiment.

Another aspect that the authors observed was that the IKEA effect and the valuation of completed products worked even for people who had no interest in “do-it-yourself” projects.

The authors describe that labor and productivity have been discovered to be central to well-being that goes beyond financial effects. A labor deprivation in the form of unemployment often has lasting psychological consequences along with the obvious financial stress.

The article also refers to the classic “instant cake mix” study done in the 1950’s. Initial cake mixes only required the addition of water thus making the process too easy and leading to the undervaluing of personal effort.

Not surprisingly, the mixes were not a great hit with American housewives. However, the modification of the recipe by adding more labor for the user such as the addition of an egg was the key reason why they became successful.

The authors go on to say:

“Build-a-Bear offers people the “opportunity” to construct their own teddy bears, charging customers a premium even as they foist assembly costs onto them, while farmers offer “haycations,” in which consumers must harvest the food they eat during their stay on a farm.”

The IKEA effect and the idea that labor and effort have to be successful are similar to seminal work done on self-efficacy by the famous Psychologist Albert Bandura. When people have the chance to complete their tasks successfully, they feel competent and in control.

“Thus our account suggests that only when people successfully complete a labor-intensive task do they come to value the fruits of that labor – the products they have created. We manipulate the success of labor in several ways to test our model – of theoretical interest to our understanding of the link between effort and liking, but also of practical interest to marketers considering engaging consumers in co-production – exploring when and why labor leads to love.” -Norton, Mochon and Ariely

For the IKEA experiment, participants were paid $5 and either asked to assemble a black “kassett” storage box or given a fully assembled box with the chance to inspect it. After assembly and observation, participants were allowed to make a bid for the boxes and told that a random price drawing would be made and if their price was below that, they could purchase the box.

Builders bid significantly higher for the boxes ($.78 vs .48) than the non-builders and also valued their products more when given a chance to buy them. Participants who had an investment in the box assembly process also liked their boxes more than the non-builders.

Action Tips:

If you want to like like your task and value it, take it to successful completion.

Have a personal investment or engagement in it in the form of labor creating greater value for you.

The more challenging the work, the more satisfaction it provides.

Incompletion or terminating a project midway can be a demotivator.

Even if you have no interest or you are not a do-it-yourselfer, you get the same satisfaction and value by the input of labor and customizing the process to make it your own.

4. The Candle Problem And Types Of Motivation: Intrinsic vs Extrinsic, What Really Works?

“Intrinsic motivation is conducive to creativity; controlling extrinsic motivation is detrimental to creativity. In other words, …[the carrot and stick] may actually impair performance of the heuristic, right-brain work on which modern economies depend.”-Dan Pink, Drive, The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us

In his TED talk, Dan Pink, the author of Drive, presents you with Karl Duncker’s candle problem. You are given a candle, thumbtacks in a box and matches. The objective is to attach the candle to the wall and prevent the dripping of wax on the table.

Many people try to attach the candle to the wall using thumbtacks but it does not work. Some people try to melt the side of the candle and attach it to the wall but that does not work either. The idea is to overcome “functional fixedness” and eventually people figure out a creative way to thumbtack the box to the wall and place the candle inside.

The trick is to have the insight to use the box as a candle holder instead of just as a holder for tacks.

Pink also refers to the research done by researcher Sam Glucksberg who used the candle problem to set up an elegant experiment on motivation. He divided the participants into two groups, and the first group was timed on how long they took to solve the candle problem.

The second group was offered rewards and received $5 if they were in the top quarter of the fastest time and received $20.00 if they were the fastest of everyone.

Surprisingly, the second incentivized group took on an average of three and a half minutes longer! This is a very contradictory result to the “carrot and stick” model of dangling a carrot and getting more motivation and better results.

In fact, this showed that when there was a creative problem, standard bonuses and incentivisation were actually de-motivating and unproductive.

Glucksberg did a slightly modified version of the experiment where the tacks were removed from the box and placed on the side making the solution obvious. He divided the participants into the timing group and the rewards and incentivizing group.

This time around, the incentivized group did much better because when the tacks are out of the box, the problem ceases to be a creative problem to solve. Rewards work great for problems where there are clear rules and a clear path. When the path is not clear and the solution needs creativity, having rewards is counter productive to motivation and solutions.

“Let’s go across the pond to the London School of Economics — LSE, London School of Economics, alma mater of 11 Nobel Laureates in economics. Training ground for great economic thinkers like George Soros, and Friedrich Hayek, and Mick Jagger. (Laughter) Last month, just last month, economists at LSE looked at 51 studies of pay-for-performance plans, inside of companies. Here’s what the economists there said: “We find that financial incentives can result in a negative impact on overall performance.”- Dan Pink

According to Pink, a new model of intrinsic motivation is slowly emerging in the work place that is replacing the carrot-stick model of extrinsic motivation. This new model revolves around the desire to do things that matter, things that are interesting and because you like to do it instead of a sense of duty and routine.

This new approach revolves around a feeling of autonomy to direct your own life, a desire for mastery to get better and seeking purpose that is something higher that yourself.

Examples of this new approach are the 20% time approach at Google where engineers spend 20% of their time working on anything that matters to them and Wikipedia where a “do it for fun” approach was more effective than official encyclopedias like Encarta.

Action Tips:

Extrinsic motivators like rewards work well where the rules and the path from point A to point B is very clear.

Rewards do not work very well to motivate when there are unclear paths, little rules and requirement for creative solutions.

5. How To Sustain Motivation: Setting Up Structures And Habits that work

“A nail is driven out by another nail; habit is overcome by habit.”― Desiderius Erasmus

Research from the laboratory of neuroscientist Ann Graybiel in MIT suggests that habits are loops that are made up of a trigger or a cue, an action and a reward.

The key to sustaining motivation in my opinion is to recognize the triggers and cues that demotivate you and lead you towards an automatic habitual loop of action and seeking rewards that are intrinsic or extrinsic.

You can also use the habit loop to motivate you by setting up triggers that motivate and inspire you and make it more likely for you to take action and follow through.

When you have your running shoes by your bed and your running clothes all laid out and a poster that inspires you in your room, you are setting up triggers or cues that motivate you towards taking action.

If you remind yourself of the intrinsic reward of how great you feel after you finish the activity, you are priming yourself to be more amenable to meeting the initial challenge of doing the task.

Extrinsic motivators such as Gamification and power-ups have been elaborately used in video games where just as you are about to quit, you get a power up or an incentive to stay in the game.

While research has shown that extrinsic rewards work better for linear, rule based activities, there are many activities like eating healthy, exercise, flossing and others that will benefit by small boosts and rewards.

Action Tips:

Understand your triggers and cues and the action and rewards behind what you are trying to accomplish.

Replace and redirect cues that demotivate you and replace with small actions and rewards that truly motivate you.

6. Respect The Gaps: Get Bored And Schedule In Down Time To Stay Motivated

“No matter how much pressure you feel at work, if you could find ways to relax for at least five minutes every hour, you’d be more productive.” ― Joyce Brothers.

A recent study in the journal Cognition at the University of Illinois at Urbana Campaign by researchers Lleras and Ariga asked the question if small breaks are essential or non-beneficial for us to keep our attention focused and avoid attention decay.

When we do a task that needs our attention for prolonged periods of time, you may have noticed that it gets increasingly difficult to stay focused.

In my opinion, our continued and focused attention is essential for the successful completion of a task and also for staying motivated. Losing focus and engagement are not very good indicators of motivation and instead they lead directly into boredom and de-motivation.

In the past, many studies have shown that our performance on tasks needing focus or vigilance show a decrease over time and is called “vigilance decrement.”

The study by Lleras and Ariga used four different groups to test their hypothesis that taking short breaks will lead to a better outcome and assist in the continued focus of the prolonged vigilant task.

The four groups were asked to perform a 50-minute task of detecting shortened lines either with or without breaks based on the group.

The control group performed the task without any breaks.

The switch and non-switch groups were shown 4 digits prior to the task and asked to memorize them (memory task) and told to respond if they saw the digits on the screen.

Only the switch group was presented with the digits or the break during the 50-minute task. Both the switch and the non-switch groups were made to recall the digits at the end of the task.

The last group was shown the digits but was told to ignore them.

Astonishingly, the switch group performed the best and avoided the phenomenon of “vigilance decrement.” The other groups showed a steep decrease in their performance over time most possibly because they did not have the same short breaks.

The study indicates that taking short breaks or even brief diversions from a task increases focus and hence the productivity of a task. I believe that when focus, engagement and productivity and feedback from the project increase, motivation is maintained.

Action Tip:

Take short breaks between long periods of activities to maintain focus, attention, productivity and motivation.

“Light be the earth upon you, lightly rest.” – Euripides

7. The theory of self-determination and The Case For Autonomy

“I’ve always tried to keep my integrity and keep my autonomy.”- Annie Lennox

Staying in charge and experiencing some degree of autonomy is an important factor in staying motivated according to psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan of the University of Rochester.

Deci and Ryan have proposed a Self Determination Theory (SDT) that explains and introduces a framework for the study and understanding of human motivation and personality.

According to the authors:

“Conditions supporting the individual’s experience of autonomy, competence, and relatedness are argued to foster the most volitional and high quality forms of motivation and engagement for activities, including enhanced performance, persistence, and creativity. In addition SDT proposes that the degree to which any of these three psychological needs is unsupported or thwarted within a social context will have a robust detrimental impact on wellness in that setting.”

I have found the requirement for autonomy, competence and relatedness to be very powerful for motivation in my own life. Whenever I had the power of choosing and feeling a sense of control or autonomy, I felt better and more motivated. My motivation increased by the continual striving to become more competent and develop my skills.

And finally, a context to express those skills that served to satisfy the need to relate and connect made my work relevant and kept the motivation levels high.

Dan Pink has expressed a similar model of motivation that includes autonomy.

Control leads to compliance; autonomy leads to engagement.” ― Dan Pink

In his book Drive, The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, Dan Pink says that the three important factors for motivation are autonomy, mastery and purpose.

Autonomy described by Pink is similar to the research from Deci and Ryan above and is the extent that you are in control of your life and are able to drive it forward to your choice and liking.

Mastery is the desire to gradually become better and continually excel in something that matters to you and has great meaning for you.

Purpose is striving to give great value and offering your service towards goals that are bigger than yourself and contribute towards a higher meaning.

8. The Four Fundamental Drives Responsible For Motivation

Motivation is the art of getting people to do what you want them to do because they want to do it.- Dwight D. Eisenhower

Nitin Nohria, Boris Groysberg and Linda-Eling Lee describe the four basic emotional drives or needs that underlie what we do and can define human behavior and motivation in their article titled Employee Motivation: A Powerful New Model in the Harvard Business Review.

The drives are:

Acquire: The need to acquire both tangible and non-tangible goods including scarce material possessions.

Bond: The need to connect deeply with other individuals and connect within the context of a group.

Comprehend: The need to understand how the world operates around us and quench our curiosity and develop skill and mastery.

Defend: The need to protect from things that we perceive as threats and defend our performance and our turf.

The authors completed two major studies to answer the question of motivating employees and in their words: “But what actions, precisely, can managers take to satisfy the four drives and, thereby, increase their employees’ overall motivation?”

The first study surveyed 385 employees of two global businesses while the second one surveyed employees from 300 fortune 500 companies.

Both studies showed that all four drives need to be met by organizations in order for them to keep their employees motivated. They also showed that the drive to connect or bond had the greatest influence on the commitment of employees while the drive to comprehend had the greatest effect on employee engagement.

They give the example of Bob Nardelli’s lackluster performance at Home Depot and attribute it to his relentless pursuit of the drive to acquire while neglecting the other drives. His relentless focus on individual and store performance neglected the need to bond for employees and their need for technical expertise and comprehension.

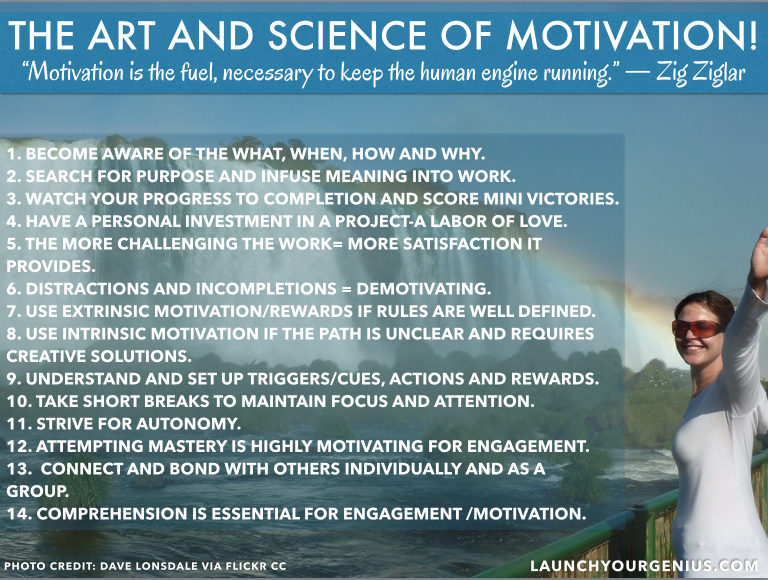

And finally, the summary of this post and a model for motivation:

1. Become aware of your unique What, When and Why you get motivated.

2. Search for Purpose and Meaning…Infuse meaning into work, however small and make it Intentional.

3. Watch your progress and go all the way to completion to stay motivated.

4. Have a personal investment or engagement in the form of a labor of love that creates value for you.

5. The more challenging the work, the more satisfaction it provides.

6. Remove or eliminate distractions and incompletions that demotivate you.

7. Use Extrinsic Motivation and rewards when the rules are very clear and defined.

8. Use Intrinsic Motivation when the path is unclear, there are no rules and you require creative solutions.

9. Understand and set up triggers/cues, actions and rewards-both extrinsic and intrinsic for habitual motivation

10. Take short breaks between long periods of activities to maintain focus, attention, productivity and motivation.

11. Strive for Autonomy to stay motivated.

12. Attempting mastery or trying to improve skills continually is highly motivating for engagement.

13. Connect and bond with others individually and as a group for motivation. Find common ground.

14. Comprehension or understanding the territory is essential for engagement and motivation.

Here is the summary in Photo form:

Now over to you! Please leave your comments below and let me know how you stay motivated and if this post resonated with you.

Photo Credit (Friends Jumping): JohnCrider via Compfight

Photo Credit (Excited about rainbows): Dave Lonsdale via Flickr CC

Comments